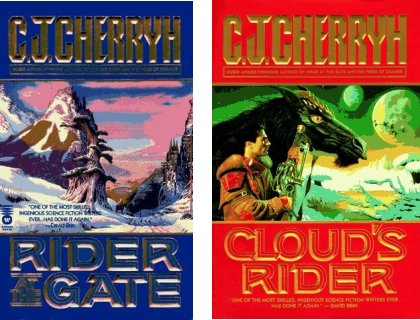

C.J. Cherryh’s Rider at the Gate and Cloud’s Rider are a slightly odd kind of science fiction. Humanity has come from the stars to colonize the planet of Finisterre, but the starships don’t come any more. (There’s no explanation of this, it’s just background.) On the planet all lifeforms can project images and emotions, and humans are vulnerable to confusion and catastrophe. But the humans have made an alliance with creatures they call nighthorses. The nighthorses give humans protection against a world that’s dangerous, the humans give the horses continuity of purpose and companionship. The preachers call in the streets “heed not the beasts” and respectable families scorn their children if they become riders, but the colony’s fragile economy and industries would collapse without them. The story begins when strange riders sweep into town bearing news of a rogue horse and a death, trouble at their heels.

It’s as if Cherryh simultaneously wanted to write a Western and undermine the tropes of the animal companion novel. The nighthorses (and yes, nightmares) aren’t much like our horses—they can be ridden but it exhausts them, and the riders mostly walk, they’re carnivorous (especially fond of bacon) and project telepathically. But the riders are a lot like cowboys, living on the edges of society, in a rough fraternity, with their feuds and vendettas and romances. Guil Stuart leaves town to avenge his partner—his business and romantic partner, as it happens. There’s a lot about the essential supplies the riders need to carry and the shelters set up to support them, about their lonely journeys with only their horses. The riders mostly protect convoys, rather than herding cattle, and they are absolutely essential to holding the colony together. All the same they’re not respectable, they’re mostly men and hard-living women, they’re often illiterate, they carry rifles; they’re people of the edges and frontiers, they have the cowboy nature.

The book is full of what the riders call the “ambient,” the telepathic background projected by the horses and the dangerous vermin of the planet. Humans can think into the ambient and read from it, but it’s mediated by their horses. The horses have names that are images like Burn and Flicker and Cloud and Moon, and they are bonded to their riders but not in a way that’s common in animal companion novels. To start with, they often won’t do what their riders want, they’re very demanding, they have their own opinions, and they twist things. They’re alien, but they behave far more like real animals than any other animal companion I’ve encountered. Their humans are shaped by the horses, as much as the other way around. Riders are free to wander the world, on their horses, other people are bound behind walls and rider protection. Riders protect the settlements but don’t belong to them. The bond between horse and rider is close and strange. It gives the riders a kind of telepathy with each other, mediated by their horses.

There’s only one scene, where a horse calls to a girl, which does read like a typical animal-companion bonding scene. It then turns the whole paradigm upside-down by having everything turn to absolute disaster. These scenes are very powerful and memorable.

It’s an interesting world with logistics that feel real, as is typical for Cherryh. The economy makes sense, and you can see how the people are hanging on to technology and industry in difficult circumstances, even in these books set at the very edges of civilization. Their ancestors had starflight, they have blacksmiths and are glad to have them. They have trucks, but they also have oxcarts. Their existence is marginal, and they can’t slip much further and continue to exist at all.

Danny Fisher, the novice rider who wants to learn better, spends most of both books cold (this is a good time of year to read these, as they’re full of snow and ice and winter mountains) uncomfortable and miserable. He does learn from experience, fortunately. He’s a lot closer to standard humanity (he grew up in a town and can read) that the other main hero Guil Stuart, who thinks almost more like a horse. Guil’s experience is contrasted with Danny’s inexperience, but Danny’s much more likeable.

The plots are complicated, and serve mostly to illuminate the way the world works. That’s OK. That’s the kind of books these are. There’s a world-revelation at the end of Cloud’s Rider that makes me long for more—but after all this time I doubt more is coming. These aren’t Cherryh’s best, but they’re interesting and readable and unusual, and I come back to them every few years.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.